Why Greatness Cannot be Planned

The Myth of the Objective

Somewhere in our lives, usually in the twenties, most of us slowly give up on the idea that if we were to discover what interests us and pursue our passion, our lives could be more meaningful and exciting. We replace that idea with a set of concrete goals; how to acquire a coveted degree and make money by joining a startup or by pursuing a career that provides stability and the means to do so.

Encouraged by parents and institutions, we don't question this shift which most of us regard as a part of growing up.

What if we are wrong about using goal-setting as the one heuristic for getting to high-level achievement?

What if we rationalise our success by measuring the milestones passed towards reaching our goal rather than examining what success means?

What if our obsession with goals effectively cuts off our ability to explore and do things for reasons different from our objectives?

These questions describe the Objective Paradox.

To achieve our highest goals, we must be willing to abandon them.

Dr Kenneth Stanely' discovered this paradox unintentionally as a part of his research in the field of Artificial Intelligence. His finding is counterintuitive and challenges many of our deep-rooted assumptions about goals, objective setting and what it means to be successful.

Dr Stanely wrote "Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned: The Myth of the Objective." and empirically proved that the objective paradox exists.

It all started when he started to breed pictures.

Breeding Pictures.

Stanely started a novel website called Picbreeder, where you could go and breed a picture. Though he didn't intend for Picbreeder to generate anything in particular, he had a hunch that people might learn something about evolution or artificial intelligence.

According to Stanely,

Breeding pictures it's sort of like breeding dogs or breeding horses. You could take a picture, you could have asked the picture to have offspring, and the offspring would be a little bit different from their parents, just like with animals. And the cool thing was, though, that if you bred a picture into something interesting, you could publish it, and it would go back to the website, and other people could see that, and they could breed from there. So people were breeding from each other's discoveries.

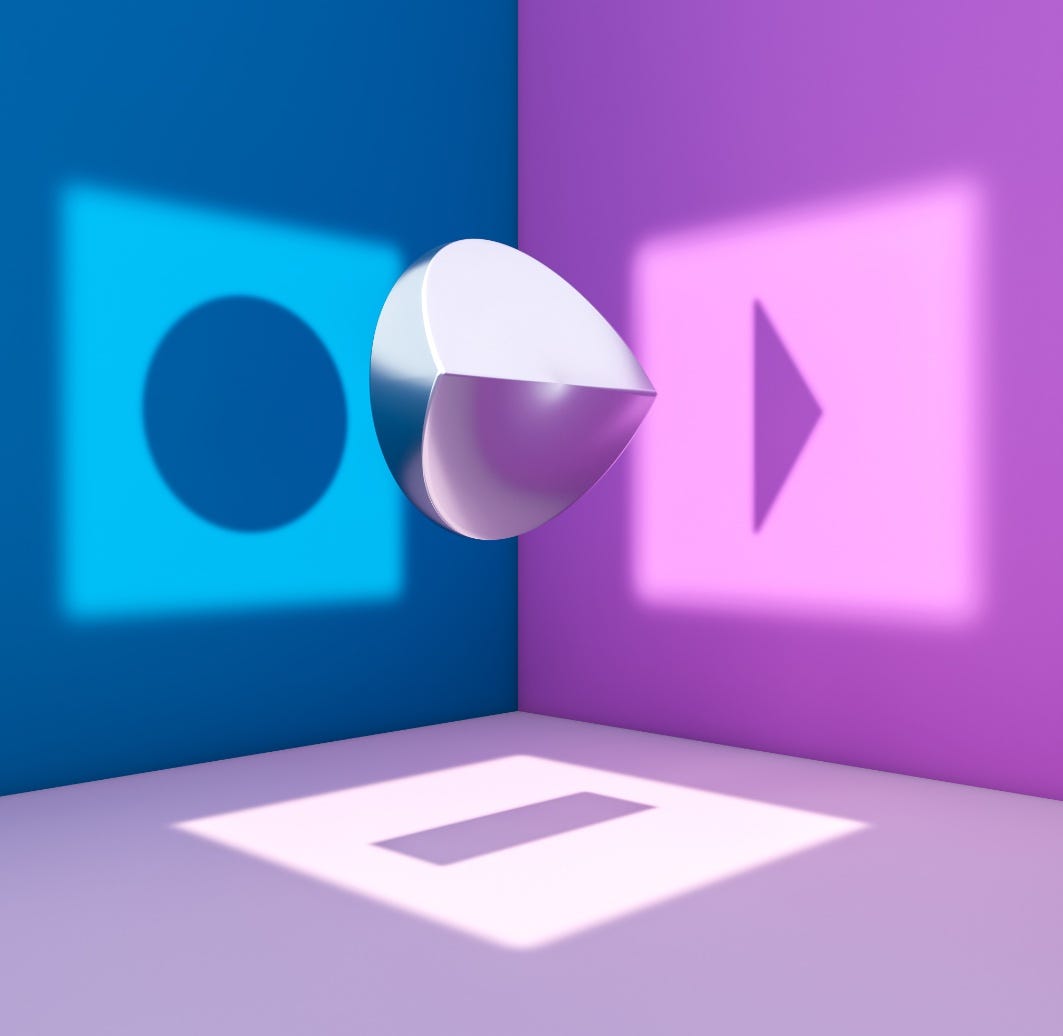

He discovered that you only find things in the long run by not looking for them. It would be self-defeating to have a particular image in mind as your objective and then try to breed towards it because you almost certainly fail.

Stanley describes how he spotted something resembling an alien face on the site and began evolving it, selecting a child and grandchild. By chance, the round eyes moved lower and began to resemble the wheels of a car. Stanley went with it and evolved a futuristic sports car.

If he had started trying to evolve a car from scratch instead of an alien race that someone else had bred, he might never have done it, which is a striking example of the Objective Paradox at work.

He tested this hypothesis rigorously. On the Picbreeder site, it took someone around 72 generations/selection steps to generate, say, a skull from an initial blob without looking for a skull. This number is tiny. When he programmed an automated machine learning algorithm with a specific objective to generate a skull and a generous 30000 iterations, it failed every time.

This is because the things that lead to the things you want don't look like the things that you want.

The things that lead to the things you want are stepping stones.

In Stanely's case, in the Picbreeder site, the stepping stone was the alien face.

In the case of the discovery of the first computer, it's a vacuum tube. No one invented a vacuum tube keeping the computer as an objective, but someone had to choose those vacuum tubes as a stepping stone to build the first computer- the ENIAC.

In evolution, for example, feathers are stepping stones and likely evolved for insulation 80 million years before they became handy for dinosaurs to fly.

Stepping stones could be unconnected discoveries like a vacuum tube in which someone made the connection to a computer. Stepping stones could be trade-offs in your career which take time and energy from your objectives and may seem a distraction. Such as writing a book, joining a startup and leaving the security of a large company, investing time in learning a new technology or in an exciting relationship that has no apparent connection to what you are doing currently.

Stepping Stones, Serendipity and Interestedness

It is necessary to set objectives to achieve short-term outcomes. Our confidence, however, may be misplaced with an unwavering belief in big hairy audacious goals (BHAG). One of the reasons for this misplaced confidence is that we are not the same people we were when we set those big goals for ourselves after ten years or even five years. These BHAGs, seem less meaningful and inspiring over time, so we search for other significant purposes. We keep searching for the 'right' goal.

According to Stanely, when it comes to breakthrough discoveries or achieving your highest goals depending on your ambition, you need to keep an eye out for stepping stones and honour 'interestedness'.

Ram, for example, felt stuck in his 'safe' and well-paying job as a PM in a well-funded startup. In his early thirties, his ambition was to be a partner in a VC fund or start his fund when he turned 40. This ambition was his high-level goal, but he had no plan of getting there.

He decided to acquire the skills, and hands-on experience he believed would help him reach his goal.

I made three moves, and each move was lateral and not a typical career progression. I took a pay cut each time, and in my last move, my pay cut was 50%. My only criterion was that the role should be challenging and exciting. When I look back, each move was correct though risky at that time.

I now realise that each move was a stepping stone, and it all came together after ten years.

If you have spent years in a field, according to Stanley, your subjective intuition matters greatly and is worth betting on within that field, even though it's hard to formulise or describe in objective terms.

He describes interestedness as the need to trust your intuition and follow a path that is interesting to you. In this path, you will discover stepping stones which may not resemble where you want to go but will serendipitously work in your favour when you least expect it, as Ram found out. Following this path is risky, and it's not for everyone.

But the payoff can be spectacular.

We can be courageous about our choices in life if we can redefine the questions we reflect on.

What am I deeply interested in?

How much of my current path is guided by my interestedness?

How open am I to discovering stepping stones, and do I recognise the ones I have?

In a world without guarantees, stepping stones may be the surest and shortest path to discovering who we are and who we can truly become- isn't that our fundamental reason for being?

Thought provoking indeed. Masterly conclusion. One of the topics I am still trying to come to terms with in the article is “ … you need to keep an eye out for stepping stones …”. Lest this leads to stepping stone paradox like objectives!!! Just recognize your deep interest and make the most of choices (stepping stones) along the way.