Sensemaking

How do we make sense in a world full of surprises.

The shape of our knowledge becomes the shape of our living. Parker Palme

In our day to day lives, we engage in active sensemaking when faced with change or an interruption. When we take up a new job, move to a new city or a country or have a new boss.

But when faced with a situation like the pandemic, which is so implausible, that it seems incomprehensible for us, sensemaking- which is our ability to make sense, is put to the test. This experience is authentic for us as individuals as well as for organisations.

Sensemaking is a term introduced by Prof. Karl Weick in his brilliant book 'Sensemaking in Organisations', which refers to 'how we structure the unknown to act in it'.

To structure the unknown, we ask ourselves the first question of sensemaking- 'What's the story here?' Or 'What's going on here?'.

To act in the unknown, we ask ourselves the second question of sensemaking- "Now, what do I do next?"

As an entrepreneur and executive coach, I find these two questions practical and effective as a starting point of sensemaking, like Alexander's sword cutting right through the Gordian knot.

I spend time helping leaders and executives make sense in these disruptive times, but I still struggle to find meaning when so many aspects of my life are interrupted or on hold.

I have learned that it helps to stay focused on these sensemaking questions. I believe plausible answers will emerge as we engage actively in sensemaking behaviours through awareness and practice.

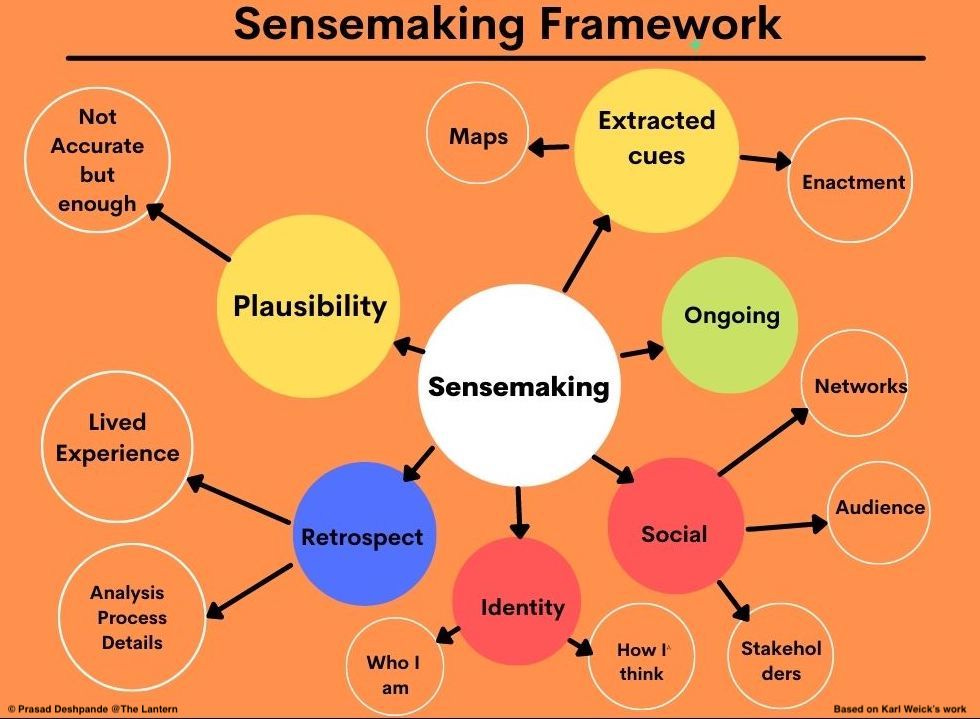

Fortunately for us, Prof. Karl Weick’s developed a framework for sensemaking which he calls the 'frame of minds about the frame of minds'.

Framework for Sensemaking

Prof. Karl Weick identified the ingredients of sensemaking that allow us as real-world practitioners to recognise where we need to pay attention and find out what we are missing in our context.

I call these ingredients pointers of clarity, as some of these pointers can make more sense in a given situation.

If you lead a team or an organisation, these pointers will help you understand and recognise where your team struggles to find meaning.

Pointers of Clarity

Answers to the question "What's the Story?" emerge from

1. Retrospect.

We are drawn to our experience to get a sense of direction. People can know what they are doing after doing it, which is at the heart of sensemaking. For example, retrospect is a well-established step in software development. An agile retrospective is a practice held regularly for teams to reflect on their way of working. Teams become continuously better at what they do.

2. Socialisation.

We are interdependent; we engage in dialogue with stakeholders and people who act on larger social units. When we speak, we speak to the audiences that we imagine in our mind.

3. Identity.

It is who we understand ourselves to be with the world around us. I coached an executive in charge of an extensive IT company infrastructure who had developed innovative ways of installing Solar power. He realised that his identity was really to be a champion of sustainable change. This realisation made so much sense to him, energised him and allowed him to grow.

Answers to the question "Now, what do I do next?" emerge from

4. Extracted Cues.

People notice things, talk about what they see with other people, develop a larger sense of what may be occurring and act. Leaders can influence how people work and go past any constraints by providing a reference point for noticing. This incident, related by the Hungarian Nobel Laureate Albert Szent-Gyorti, wonderfully explains how we make sense when we are lost.

Lost in the Alps

A young lieutenant of a small Hungarian detachment in the Alps sent a reconnaissance unit into the icy wilderness. It began to snow immediately, snowed for two days, and the company did not return. The lieutenant suffered, fearing that he had dispatched his people to death. But on the third day, the unit came back. Where had they been? How had they made their way? Yes, they said, we considered ourselves lost and waited for the end. And then one of us found a map in his pocket. That calmed us down. We pitched camp, lasted out the snowstorm and then with the map, we discovered our bearings. And here we are. The lieutenant borrowed this unique map and had a good look at it. He found to his astonishment that it was not a map of the Alps, but a map of the Pyrenees.

Karl points out the intriguing possibility that when you are lost, any old map will do. The map served as a starting point for the soldiers to act, pay attention to the outcomes of their actions or cues, and take further action till they reached home.

5. Plausibility.

Sensemaking is not about truth and getting it right.

It involves coming up with a plausible understanding—a map—of a shifting world; testing this map with others through data collection, action, and conversation; and then refining, or abandoning, the map depending on how credible it is.

When the pandemic interrupted the office, organisations developed different maps- WFH( work from home), Hybrid Work or WFA (work from anywhere).

Organisations are still making sense of each of these maps, and there could be more, but we are moving forward. There is no ideal map or the most accurate one for sensemaking. It is plausibility rather than accuracy, which is the ongoing standard that guides learning.

How do we get better at sensemaking?

By paying attention to who we are and how we think. Our mindsets influence our behaviour and the shortcuts or heuristics that we prefer.

By recognising that we are interdependent. And that we need to socialise and work with people who think differently. We need to honour differences and not move away from them.

To treat the constraints that we face as self-imposed and find a way.

To appreciate the wisdom of our 'lived experience" and use retrospect to get a sense of direction and not tie us down.

To settle for plausibility and not accuracy and move on. That's the only way to deal with ambiguity.

To understand sensemaking is an ongoing process, and what made sense yesterday may not make sense today as the context has changed and your priorities might have changed.

Bouncing Back

Our ability to bounce back depends on how we navigate interruptions and deal with surprises like this pandemic. It is also safe to assume that there will be other events down the road, large or small, that will interrupt us.

Sensemaking is about doing. It's about taking small actions in our day to day lives that guide us forward, making sense as we go, amid surprise and uncertainty. As leaders or members of teams, these small actions have significant consequences.

Really an interesting read ! The framework and the 2 basic questions : what and what next is the crux of making sense to any situations.. whether at work or in any other social context !

Superb article Prasad. The two primary constructs of Sensemaking will help all of us. I also like the map story of Alps - "when you are lost any old map will do"!!