Second Curve Thinking

How to live a fuller life.

Young brains are designed to explore; old brains are designed to exploit.

Alison Gopnik

A Familiar Story

SD and I were having lunch at the 19th hole, and SD was looking quite pensive, which was a bit surprising since he had played this round to his low handicap, which is very satisfying for a golfer. SD had a very successful career. He qualified as a mechanical engineer and rose rapidly from the shop floor to head two large markets for a European Multinational as the MD.

He couldn't continue as the MD because of the pandemic. Rather than going back to headquarters, he decided to leave and become the overall head of manufacturing for a German multinational. It was a meaty role, setting up ‘smart’ factories, building an organisation for the future, and I was happy for him. I was puzzled and more than a little bit curious when he told me that he had resigned from the role.

He said Industry 4.0; the ‘smart’ factory was about the intelligent networking of machines and processes.

I can't provide leadership and, at the same time, start learning about electronics, the internet of things, machine learning. Just knowing the basics is not enough. The people in my team are much younger and way more intelligent than me. I can't lead if I can't keep up.

SD's setback was of his own making, a familiar story of many high achievers who are seemly stalled, lost at sea, with no wind in their sails.

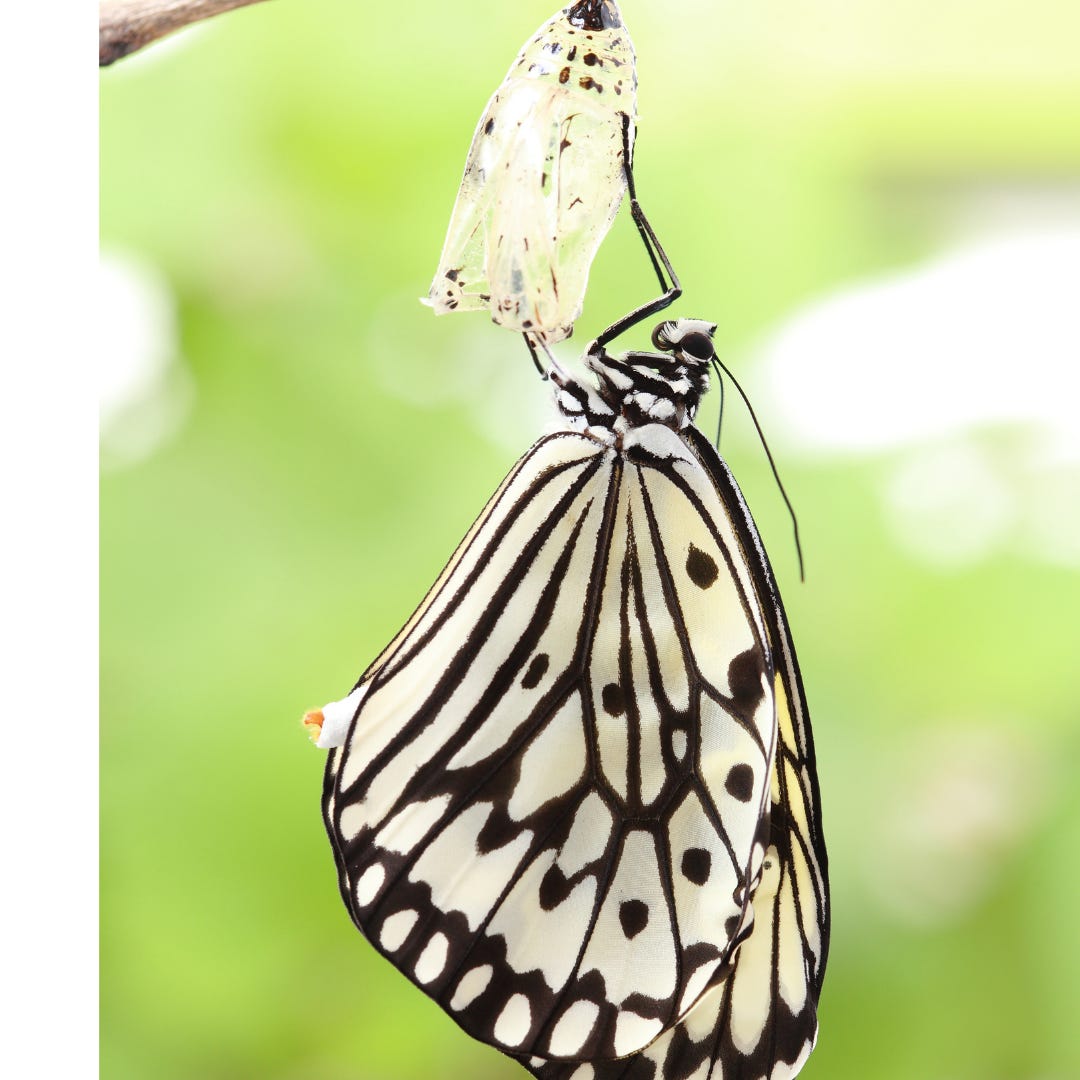

Sigmoid Curve

There is no escape from the sigmoid curve, a powerful metaphor that explains SD's inevitable decline. The only variable is the length of the curve. The second curve has to start before the first wave peaks; the catch is knowing when and transitioning to the second curve before the inevitable decline.

But as Charles Handy says

Success puts blinkers on us, discourages doubt, reinforces itself. Only in retrospect can we look back and say, 'That was it, that was the peak, that was when we should have started to think anew.'

An Act of Courage.

But little Mouse, you are not alone, In proving foresight may be vain: The best-laid schemes of mice and men, Go often awry, Robbie Burns in an Ode to the Mouse.

SD told me that he had a sense that he wouldn't be able to continue indefinitely as an ex-pat MD; he knew it didn't make sense in the long term. But he imagined he had time for another tenure before thinking about the future.

If we prepare for the future, it doesn't always have to be this way.

Second curve thinking is counterintuitive; to be willing to see past one's success, to be ready to reset and explore unchartered territory. It can be risky as shifting to a new curve may not always work out.

How does one cultivate second curve thinking?

It's essential to recognise that second curve thinking is an act of courage not borne out of desperation but from a clear understanding that everything changes.

Even one's intelligence changes over time, diminishing in some aspects and increasing in others as we age. A fact that otherwise would have devasted SD had he not understood the nature of the change.

Fluid and Crystallised Intelligence

In the early 1940s, Raymond Cattell introduced the concepts of fluid and crystallised intelligence. Cattell defined fluid intelligence as the ability to think and reason abstractly and perceive relationships between things without prior practice or instruction. Fluid intelligence consists of the capabilities that make one a flexible and adaptive thinker able to respond to any situation but especially new ones and is not dependent on prior learning, life experiences or education.

Crystallised intelligence builds from past experiences and learnt facts and amounts to judgement skills that accumulate as we age. It is the essence of wisdom.

Fluid intelligence declines significantly throughout adulthood, whereas crystallised intelligence improves. Careers that rely primarily on fluid intelligence tend to peak early, while those that use more crystallised intelligence peak later. Because crystallised intelligence depends on an accumulating stock of knowledge, it tends to increase through one's 40s and does not diminish until very late in life.

For example, Dean Keith Simonton has found that poets—highly fluid in their creativity—tend to have produced half their lifetime creative output by age 40 or so. Historians—who rely on a crystallised stock of knowledge—don't reach this milestone until about 60.

Although we do not fully understand why fluid intelligence declines, it is highest relatively early in adulthood and diminishes starting in one's 30s and 40s, explaining why today's startup founders are so ridiculously young - in their early twenties. Zepto's founders are 19 years old. This decline may be related to changes in the underlying changes in the brain from the accumulated effects of a disease, injury, and ageing or lack of practice (Horn & Hofer, 1992).

Old Brains and New Brains

Since everything changes, preparing for one's second curve isn't about waiting till one nears retirement before making a change; it might be more thoughtful and wiser to make the jump to the second curve earlier, in one's thirties or forties. Based on what you do, be ready to experience multiple second curves.

Most people don't think this way. Like SD, many leaders I coach believe that their experience gives them an edge, and all they have to do is work harder to succeed. Many will indeed achieve by pushing through, but the cost will be high.

According to Arthur Brooks,

Each peak of our success yields a shorter period of satisfaction, spurring us to work even harder to perform just as the ability to reach each new peak declines with age. This addiction to relentless achievement is ultimately bound to yield disappointment.

Second curve thinking is about redesigning one's life to rely more on crystallised intelligence as fluid intelligence diminishes.

SD recognised that his desire to experience his former work highs was driving his decisions and wisely stepped back from his role even though his organisation believed he was the right man for the job.

He has redesigned his life by choosing a more advisory role- building on his years of experience in scaling up manufacturing businesses. A function that also focuses on mentoring and coaching younger leaders allows him to stay in touch with the latest technical developments and learn from the best- those much younger than him. He also realised that he possessed fungible skills and was still very much in demand but not how he used them in his first curve.

Making the Leap

The time to change is before there is a need to change. Anon.

I shared SD's story with a group of technology managers in their early and mid-forties, experts in mechatronics. They, too, shared their fears of not keeping up with new technical advances, how younger people were so much better than them at core skills and how they were worried about being irrelevant. They asked me how to transition to the second curve and keep growing.

There are no templates, only a few pointers.

Focus on developing the capability of others, find out opportunities to share your tacit knowledge, say yes to every opportunity.

Focus on developing relationships at work and professional associations and forming genuine friendships, not just a social media network. Pay more attention to relationships at home.

Know yourself. Prepare an inventory of your skills and strengths; you will be surprised at how much you know. Identify what you don't like to do and assess if this is a weakness.

Second curve thinking is accepting that everything changes especially our abilities and intelligence. The search for our second curve is the search for how best to adapt to these changes so that we can use our accumulated expertise and experience to keep growing in wisdom and to be more fulfilled.If we are able to make the choice to move to a second curve, we should do so gladly despite the initial discomfort. Not everyone is so fortunate.

Love this article for its relevance in the corporate world ! I think everyone must read this to imbibe and understand the timing for their “second curve” learning. Very well written! Thank you Prasad !